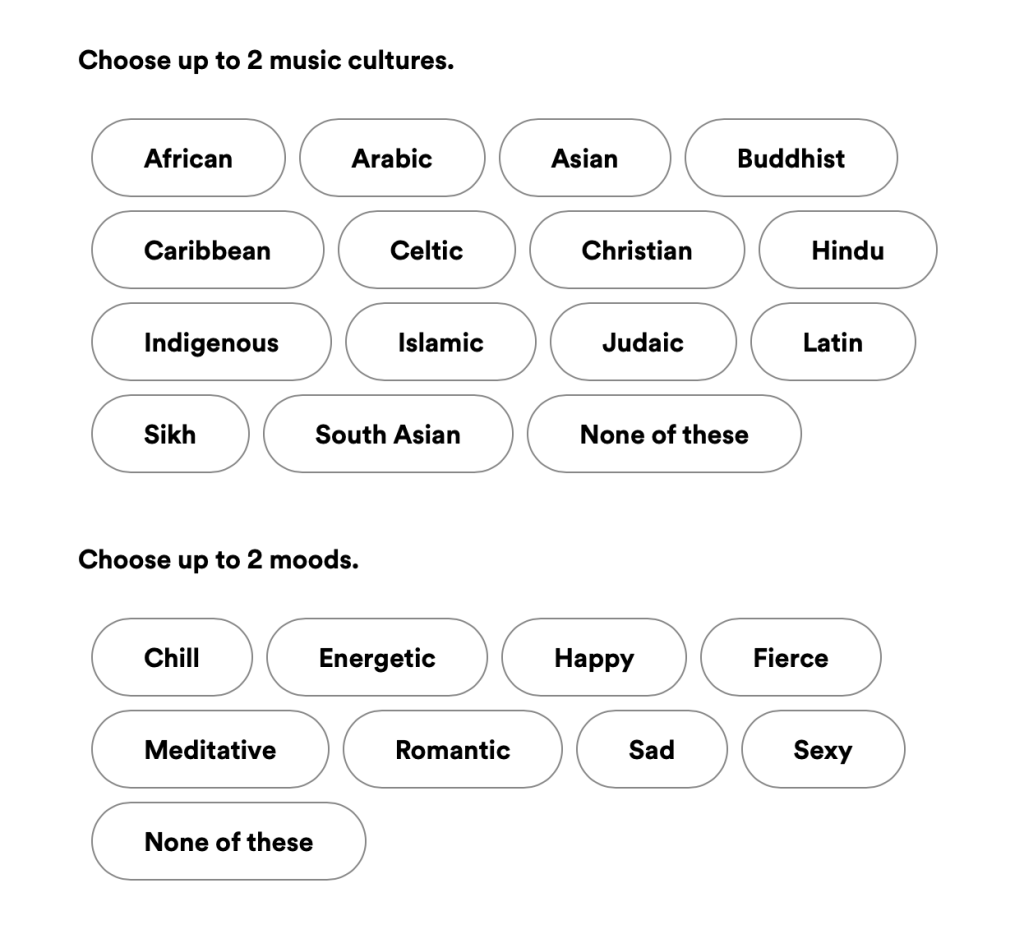

When you upload a track to Spotify you’re given an opportunity to write a short pitch to have the music considered for one of Spotify’s three thousand “editorial” playlists. The pitch format is strict: check a few boxes about what instruments are featured (e.g. “synthesizer”, “violin”, “bouzooki”, “sampler”…), what music culture you’re operating in (e.g. “Celtic”, “Hindu”…), whether it’s a live or studio production, whether there are lyrics or not, what’s the musical mood (“Fierce”, “Meditative” . . ) and which three music styles best describe the sound. This information helps Spotify’s machine learning software sort the music by instrumentation and style (despite being incapable of listening). But the most important part of the pitch is where it asks for a brief note (no more than 200 characters) about the process of composing the track and what inspired it. This information is not for the AI but for Spotify’s (allegedly) human editors who sift through track submissions and decide which lucky ones belong on playlists such as “Peaceful Piano”, “Deep Listening”, or “Lofi Beats.”

But it’s difficult to write about inspiration if you don’t believe in it. As I see it, process is what composers/producers actually do, while inspiration is what they believe guides they’re doing. So framing artistic practice in terms of inspiration, as Spotify’s pitch guidelines do, may be an example of what you want the work to be about, rather than what it is. Think about how you work: Do you work out of inspiration or out of curiosity in the sense that it’s by making something that you answer the question: What can I do with a set of sounds, what can I make given my limitations of skills, know how, and experience? Of course curiosity sometimes leads to moments of inspiration–This unexpected sound is so cool!–but mostly each project is a way to imperfectly finagle the kind of music you would to like to listen to. So to answer Spotify’s question about what inspired the music: rather than make up a reason why I made it, I explain how I made it–how it’s structured and how this structure shapes the music.

Talking about process may not be an inspiring response to a question about inspiration, but it may be a more accurate accounting of how music comes to be. Process is music production’s key through-line in that it enacts your workflow inside your musical system. This workflow is what generates the materials for new music–it’s new music’s prime mover. To illustrate, in my Electronic Music Production Concepts Database almost all of the ideas from producers concern details of process rather than inspiration’s vague sources. (This isn’t surprising since musicians are by nature and training practical and experience-oriented.) When I did a word search for “inspiration” I found it appearing just three times, while “process” appears forty-four times. Two instances of inspiration appear in the writing of producer Mark Fell, who, ironically, is anti-inspiration in how he frames creativity as outward-focused curiosity rather than an inward-focused searching:

“I want to promote a description of creativity as a process of attunement to the material environment, not an isolated or inward journey further into one’s thoughts or mind or soul. In this sense, the description I want to promote is one driven by a critical curiosity rather than a thing called inspiration…which I know nothing of” (Mark Fell, Structure and Synthesis: The Anatomy of Practice, p. 21).

Inspiration is also mentioned by producer Ital Tek, who sees it as “as a muscle I flex.” He explains how this muscle gets a work out through the happy accidents of practice:

“The way I work is to create a huge amount of content/versions/takes whatever you want to call it and then hone it down over and over. I’ll get inspired by some happy accident when I unplugged a guitar and it made a weird thud through the fx chain, then turn that into a percussive patch in Ableton.”

But for the most part, producers refer to musical process and musical processing as the main drivers of their workflows. Here are a few examples from the Database:

“Sound truly gets me inspired. It’s what I react to. A patch I created, then sent through this FX chain, then sampled and put into simpler and back out through another FX chain. That method of experimenting inspires me constantly.”

“My compositional process can be broken down into two steps. The first is processing the source material. The second is determining what to do with the prepared material. Using computers and outboard gear, it is possible to process material in an infinite number of ways, so you could say that processing could go on forever.”

“It’s like a process of incremental discovery everyday.”

“I usually sneak up on myself, like I start designing an instrument and then the songs come out by accident as a result. It’s weird–sometimes I’ll go in the studio and something will come out by itself, but the process and the method of it is really important to me.”

“I will use objects, like cymbals, mallets, rhythmic pulses, or granular textures and then use the impulse file to impose the amplitude and frequency of that sound and convolve it to the incoming audio. I have discovered so many interesting sounds with this process.”

“Even in the approach to Monteverdi, I worked on the fragment, I would say even on the fragmented nature of the creative process: I worked on sound tissue sampling and processing an enormous amount of material taken from all releases, on vinyl and tape…”

“I’m constantly exploring stuff on different scales and then the stuff that interests me ends up on different compositions, potentially. But even if things don’t get used, often you learn from them, or you learn what you like or don’t like, the process.”

In sum, non-practitioners who wonder about what inspires artistic process–What’s the work about? What are you trying to achieve with it?–make an error in assuming that inspiration itself is a work’s main driver. In non-representational arts like music, the most inspirational source of ideas is the process of making itself. It’s by creating the conditions for making music and tinkering away within this environment that you create opportunities for discovering new ideas.

Leave a comment