As a percussionist, I don’t have a favorite musical instrument, which makes sense because percussionist are, by training and maybe by temperament, generalists. We learn how to strike and vibrate a great many instruments–from tympani, djembes, and snare drums to marimbas, gongs, and glockenspiels–without playing favorites. Each instrument is a world and requires its own specialized techniques of playing using sticks, mallets, hands, and fingers. As with any instrumentalist, percussionists obsess about touch, tone, and timing. Notice a percussionist’s finesse–pay attention to their sound, their feel, their fluidity, their dynamics, and their decision-making. In the acoustic musical world, being musical is less about the instrument a musician is playing and more about how they’re playing it and the ineffable qualities they bring to that playing.

This primacy of sound over a sound’s source is an apt characterization of electronic music production in that producers too are generalists who explore so many ways to make or capture a sound that is acoustic, electronic, sampled, synthesized, or hybrid. That’s one reason I enjoy production as composing: it’s about a plurality of sounds and the many methods by which to create both sounds and the worlds they inhabit. Say you want to make an ethereal pad. You might work additively, beginning with a sine wave and build up from there, adding texture, overtones, and ambiences to shape something. Alternately, you could work subtractively, beginning with an already textured sound–what the producer Fred Gibson (aka Fred Again..) calls starting “from a point of real intricacy”–and then remove from it, the way a sculptor chisels a stone to reveal a shape. You could filter out the sound’s overtones and ambience using EQ to leave something like a sine tone, but with vestiges of intricacies still felt underneath. A third way to make your pad could be to take an acoustic soundscape recording–say, a rainstorm–and devise a way to highlight its inherent pitches, maybe by creating a sampler instrument with it. In production, there are many routes to an intended destination. As Tame Impala notes, “You don’t need something to get something, you can get there some other way. You just have to look.”

Not only are there many routes to a sound, there’s also many devices for making this happen. Most of these devices are synthesizers, effects processors, and sampler instruments. Often several devices types are integrated into a single instrument.

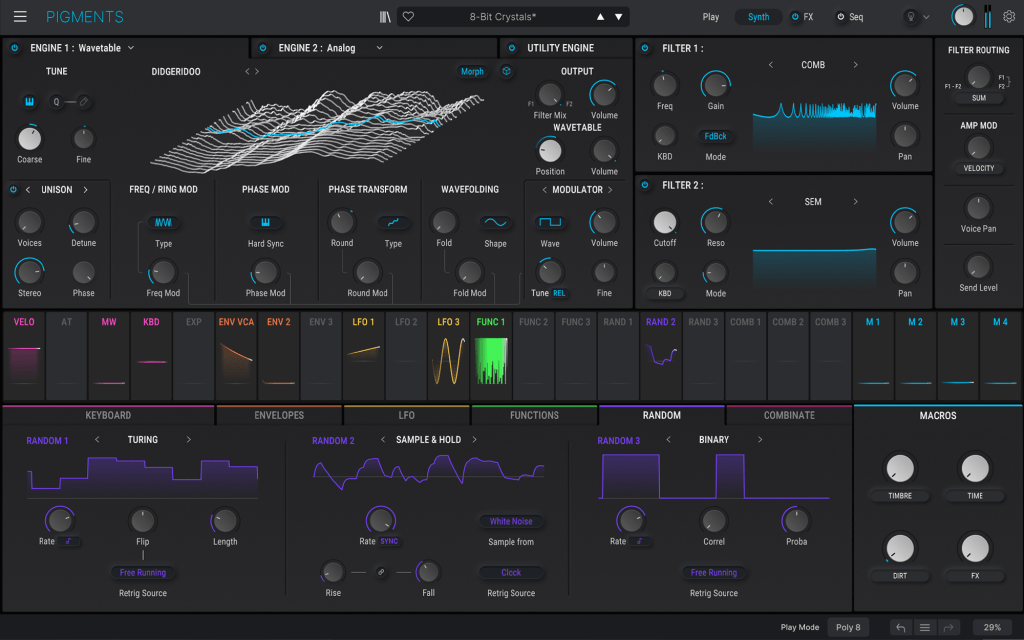

Figure 1. Arturia’s Pigments.

For example, Arturia’s Pigments (Figure 1) synthesizer includes a sampler into which audio files can be imported to use as sound sources. Along with its sampler, Pigments has multiple oscillators, effects, and modulators that can be connected together. For example, you could combine your sample with a sawtooth tone and a reverb, then modulate aspects of each of these three elements. While having so many sound design options in a single software instrument would have been impossible 30 or 40 years ago, today it’s a common integration and a reminder that, in one way or another, a software instrument can do everything you need to do, and more.

Each software instrument or effect excels at doing different things and just as importantly, has a different feel. Many either evoke or exactly copy classic analog hardware, such as 1970s synthesizers or 1950s compressors. For example, Sequential Circuits’ Prophet 5 keyboard, released in 1977, now has numerous software clones, such as Arturia’s Prophet 5-V. Or Teletronix’s LA-2A compressor, released in 1965 and whose rich sound has been a staple of recordings ever since, has emulations by UAD, Waves, and other companies. However, devotees of making music entirely ITB or “in the box” of the computer, without using music hardware, might argue that production’s cutting edge is with software instruments that forgo emulating the circuit paths of vintage gear (and their retro looks, via skeuomorphic GUIs) and instead celebrate their own digital uniqueness. Pigments fits this description, as do three other examples: Xfer Records’ Serum, u-he’s Zebra, and Slate & Ash’s Landforms.

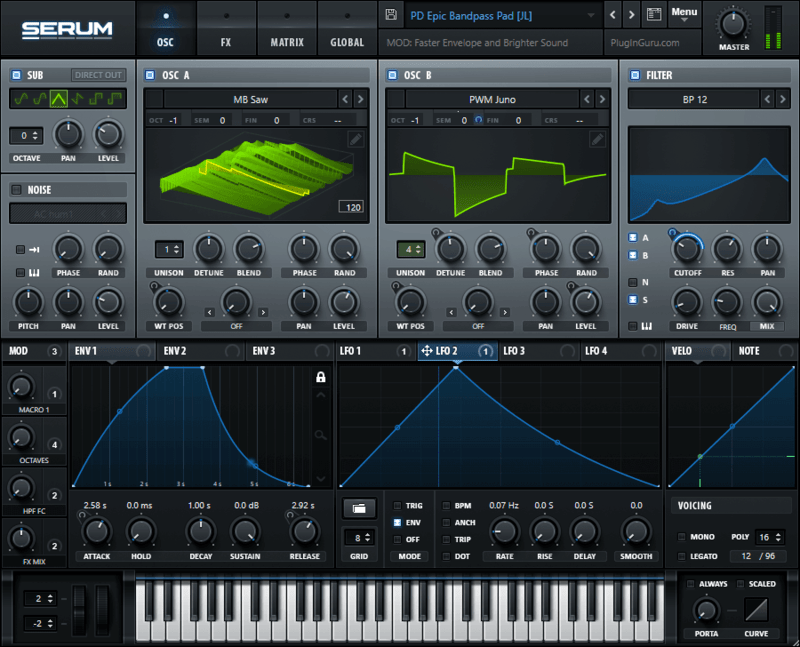

Figure 2. Xfer Records’ Serum.

Serum (Figure 2), designed by self-taught programmer Steve Duda, is an elegantly designed wavetable synthesizer widely considered the successor to Native Instruments’ Massive, which was released in 2006. Serum’s main features are its 8 LFOs which are easily mapped to any parameter on the instrument. Serum is versatile in that you can make all kinds of sounds with it, from squelching basses to glassy leads. (Check out Virtual Riot’s Serum-based tutorials, if you can keep up.) The synthesizer is an excellent self-teaching tool in that its click-to-drag-this-to-that layout allows you to see most of your modulation work on a single page.

Figure 3. U-He’s Zebra.

Zebra (Figure 3), the brainchild of Urs Heckmann and his company u-he, is less a single synthesizer than a modular synthesis environment that offers additive, subtractive, FM, and physical modeling synthesis as well as many, many modulation and effect types. Unlike hardware modular synthesizers, Zebra’s patching and routing of sound generators and modulators is done on a single page (as with Serum) and the instrument’s audio path has a pleasing visual logic, running from top to bottom, without the (virtual) tangle of modular’s wires. What makes Zebra compelling is the sense it creates that you’ll never get to the bottom of what it can do. Put another way, Zebra’s sonic possibilities always seem beyond what you can imagine, which gets you rethinking what exactly you can imagine.

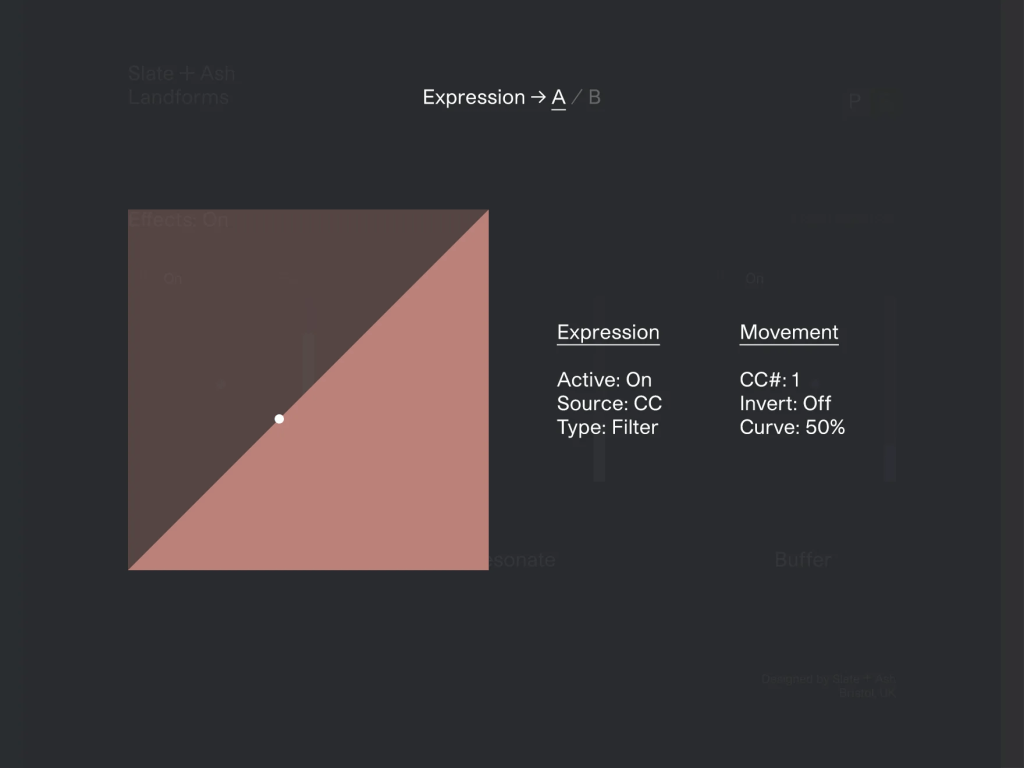

Figure 4. Slate & Ash’s Landforms.

Finally, Landforms (Figure 4) is a sampled strings and woodwinds library from Slate & Ash. The instrument contains hundreds of recorded textures, ranging from solo violin to brass sections, from long sustains to quick pulsations to wavering, gossamer harmonics. In addition to its performed textures, Landforms’ effects page has processing options such as tuning, signal processing, and reverbs for warping your timbre. The sampled sounds sound acoustically life-like–they’re so replete with micro-variations that you can simply play a single note and hear something interesting–yet they can be further morphed and squeezed into various spaces. The GUI of Landforms doesn’t look like any recognizable electronic musical instrument: a minimalist box with small controls is all you’re given to play with.

I like each of these software instruments in that they invite me to explore them by interacting with their possibilities and serendipities. Is one instrument better than another? Is Serum superior to Zebra? So far, no, although I’m not an advanced user of any of them. Even so, the more I work with them and other software instruments the more I realize that what makes an instrument musical is how I can interact with it. As with playing percussion, this interaction is a function of my own energy and know-how, but also of how an instrument is set up, how it feels, how it sounds, and what kinds of fluidities, dynamics, and decision-making it encourages and makes possible.

In sum, think about a few qualities in software music instruments:

It does one thing really well. For example, the software mimics a real instrument, like Modartt’s Pianoteq virtual piano, or else celebrates being synthetic, like u-he’s Zebra.

It has a GUI that makes visual sense. Ideally an instrument doesn’t hide any of its functionalities and so you can figure it out, more or less, just by using it.

Are its parameters automate-able? A software instrument needs to be MIDI-mapped controllable in every respect because, after an inspired live performance, editing via careful automation is the second best way to generate moving details within a part.

It generates genetically related sounds. Some instruments, such as Sonic Charge’s Synplant can generate novel variations of the sound you’re on. This may turn out to be a powerful use of AI in music production.

It’s unfathomable. Just as we sense ineffable qualities or spirit in the playing of another musician, we notice something like soul in software, even though its coded logics are not our embodied ones. So there’s a disconnect between action and result when we use software instruments because we can’t get to the bottom of our tools: we’re never achieving what we intend to achieve the way that we do when we play an acoustic instrument and get reliable results. But maybe this disconnect keeps production interesting in that even as we miss sounds intended, unintended ones appear along the way. Wow, that sounds cool! Let’s go with that… Software instruments are ideally unfathomable, their potentials a perpetual reminder of how much more we could do, someday.

Leave a comment