If you played a musical instrument when you were growing up you spent years getting to know how the instrument worked and how to work with it. It took time—concentrated lesson time with teachers and diffuse time alone, practicing for thousands of hours. You learned good tone, technique, repertoire, and how to play this repertoire in a stylistically appropriate way. Whether you aspired to become a classical clarinetist, rock guitarist, or jazz drummer, achieving skill was a long road to travel. (Virtuosity is a different road about which I know nothing.) It takes years, usually decades to feel like you can express yourself through an instrument–to feel as if you’re one with what is in fact a mechanical contraption that’s always separate from you.

Skilled musicians have a relationship with their instruments that’s deep enough that the instruments feel like extensions of their bodies. The drum and drumstick extend the drummer’s hand, the violin and its bow allow the violinist’s fingers to sing, the trumpet player’s horn and its mouthpiece amplifies breath and turns it into tone. Having a relationship with a musical instrument means learning to play at the interface point at which you and your chosen acoustic sound-making machine meet and interact.

Over time, this meeting and interacting leads to your developing a tacit knowledge of an instrument’s expressive potentials—a sense of what you can do with it. Drummers and percussionists, for example, have a unique understanding of the phenomenon of bounce. The way their sticks bounce depends on the instrument the sticks are striking, as well as the sticks themselves. (Sticks with soft heads on them, called mallets, don’t bounce the way sticks do.) The varied surfaces of snare drums, bass drums, timpani, cymbals, gongs, and marimbas each have distinct bounce demands. Some of these surfaces are tensioned (e.g. timpani heads), some aren’t (e.g. marimba bars), and each surface in vibration reacts differently to sticks and mallets. Drummers then, not only keep time and accent it; they also continuously adjust the bounce of their drum strokes to the ever-changing vibrating state of their instruments. The next time you notice a jazz drummer’s right hand keeping time on a large cymbal known as a ride cymbal, know that the drummer is smoothly “riding” the vibrations of the cymbal through bounce.

•

Now let’s turn from playing acoustic instruments to playing virtual (software) ones. If acoustic musical instruments are extensions of our bodies and require a tacit knowledge of their expressive potentials that takes time to develop, what can we say about virtual instruments? “Playing” a virtual instrument deserves quotation marks because the nature of the playing is, in my experience, unlike the playing of acoustic instruments. Let’s take a look at how this is so.

First, when I play a virtual instrument my touch doesn’t determine the sound I make. When I play a MIDI controller–which I do as much as possible because I like keyboards–I’m not making a sound, but rather triggering one. This means that some of my know-how about how to make sounds is blunted from the get go. When I play a controller, my sense of touch doesn’t get to directly touch the music. This is a problem. It’s in this way that a virtual instrument can mute some aspects of acoustic musicianship.

Second, when I play a virtual instrument and record the results anything I play is provisional in the sense that I can change it after the fact. For example, I’ll fix errant notes, re-shape dynamics, and move pitches up or down to make new chords long after I played them. This isn’t a problem, it’s a good thing! MIDI is malleable, and finessing it is a way to retrospectively inject touch into the music. Most significantly, I can change the sound of the virtual instrument after recording a part. This is how, with some tweaking, a lead melody becomes a bass line, or piano chords become string orchestrations. It’s no understatement to say that using a single MIDI part to generate multiple instrumental lines after the moment of recording is one of the producer’s most powerful practices because it allows one to try out many options very quickly.

Third, unlike my longstanding relationship with the piano, I don’t stay with a virtual instrument for long; instead I move among multiple instruments constantly. I try new ones and then circle back to old ones, comparing the functionalities of each, waiting for an Ah-ha! moment when it becomes clear that this instrument is the one I’m going to commit to. But this hasn’t happened. What happens is that I focus on one instrument if I find a path forward with it. Recently, for example, I made an instrument out of one harmonium drone. Maybe I’ll make a few pieces with this virtual harmonium instrument. Or maybe the instrument will become a building block for another sound down the road. We’ll see.

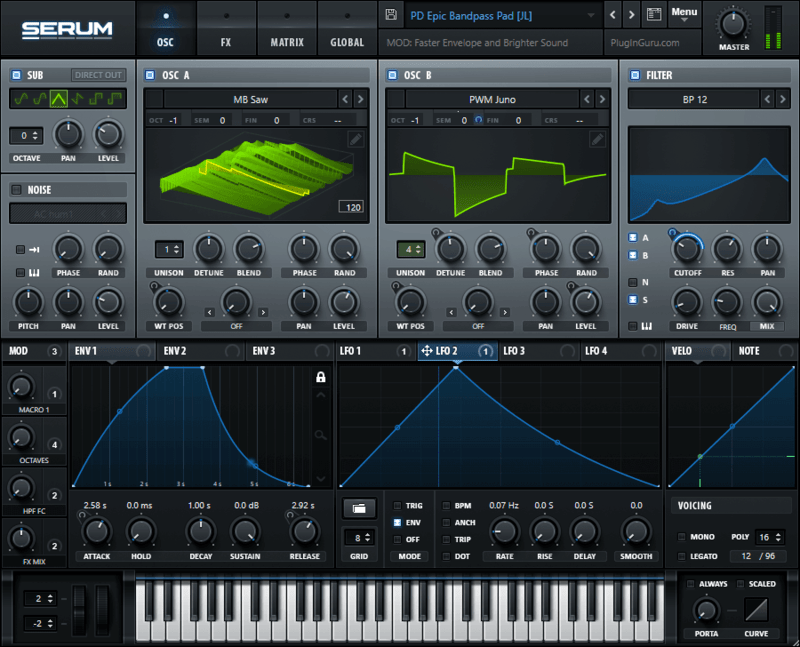

A fourth point about playing virtual instruments is that my relationship with them consists of slowly building up a memory of their uses. This memory is more visual than kinesthetic–like a remembering of which controls and parameters are where and how I’ve used them to make interesting sounds. This memory is helped along by my practice of saving sounds I’ve made or altered while working. The practice is: whenever working with an instrument try to save at least one new sound, with the goal of slowly accumulating a library of favorites you can return to. This library of sounds is a tacit knowledge externalized in the software. Whenever I open an instrument I’m always surprised by how much I’ve saved in its sound banks. (What sounded cool then, tends to still sound cool.) Over time, a producer will remember generalities of what they’ve done with this instrument or that effect. There’s a bunch of wobbly pads here, or I made some interesting grainy delays with this. Saved sounds and effects can also be connected into chains to make Frankensteinian hybrids. Saving such chains adds to a producer’s library and builds a repertoire of ways various instrument and effect combinations have been used.

In sum, the relationship I have with virtual instruments is more about memory that embodied knowledge. As I work with them, I build a sense of the things they can do. This is a different kind of musicianship than that required to drum, or play piano, but not completely different. When we play acoustic instruments it’s a physical encounter with a resistant machine, and when we play virtual instruments it’s a non-physical encounter with an opaque piece of software. Both ways of making music require a commitment and sustained energy over time to get something feelingful going, to somehow alchemize vibration, oscillation, and synthesis into meaningful sound. The power of an acoustic instrument is that it can only be the instrument it is, while the power of a virtual instrument is that it can be anything you want it to be. That’s uniquely exciting: a beckoning from sounds and musics which we haven’t yet figured out how to make.

Leave a comment