“Perhaps the most curious thing about natural patterns is that they come from a relatively limited palette, recurring at very different size scales and in systems that might seem to have nothing at all in common with one another” (12).

“What is a pattern, anyway? We usually think of it as something that repeats again and again. The math of symmetry can describe what this repetition may look like, as well as why some shapes seem more orderly and organized than others. That’s why symmetry is the fundamental scientific ‘language’ of pattern and form. Symmetry describes how things may look unchanged when they are reflected in a mirror, or rotated, or moved. But our intuitions about symmetry can be deceptive. In general, shape and form in nature arise not from the ‘building up’ of symmetry, but from the breaking of perfect symmetry—that is, from the disintegration of complete, boring uniformity, where everything looks the same, everywhere. The key question is therefore: why isn’t everything uniform? How and why does symmetry break?” (22).

“Endless forms most beautiful” [Darwin] (26).

“Pattern comes from the (partial) destruction of symmetry” (32).

“It’s not hard to see where this magic ingredient lies. The shape of a tree is complicated, and we can’t easily describe it in the same way as we might describe a square or a hexagon. But we can give a very concise description if we focus instead on the process that produces the shape. A tree shape might be said to be ‘a trunk that keeps branching’” (62).

“The reason why a tree’s shape ‘feels’ pleasing rather than incomprehensibly complicated is, I would argue, that we sense the simplicity of the algorithm needed to make it” (62).

“The wave is a pattern in time as well as space: it is a constant pulse, a periodic coming and going. When one wave meets another, their interference can create spectacular new patterns. But perhaps most astonishing of all are waves that organize themselves from sheer disorder or from seemingly inexorable, one-way processes: from the chemical reactions between molecules moving at random, say, or the collisions of wind-blown sand. In such cases, waves can imprint themselves on matter with a flamboyant ebullience” (164).

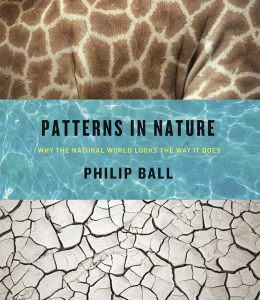

Philip Ball, Patterns in Nature (2016)

Leave a comment