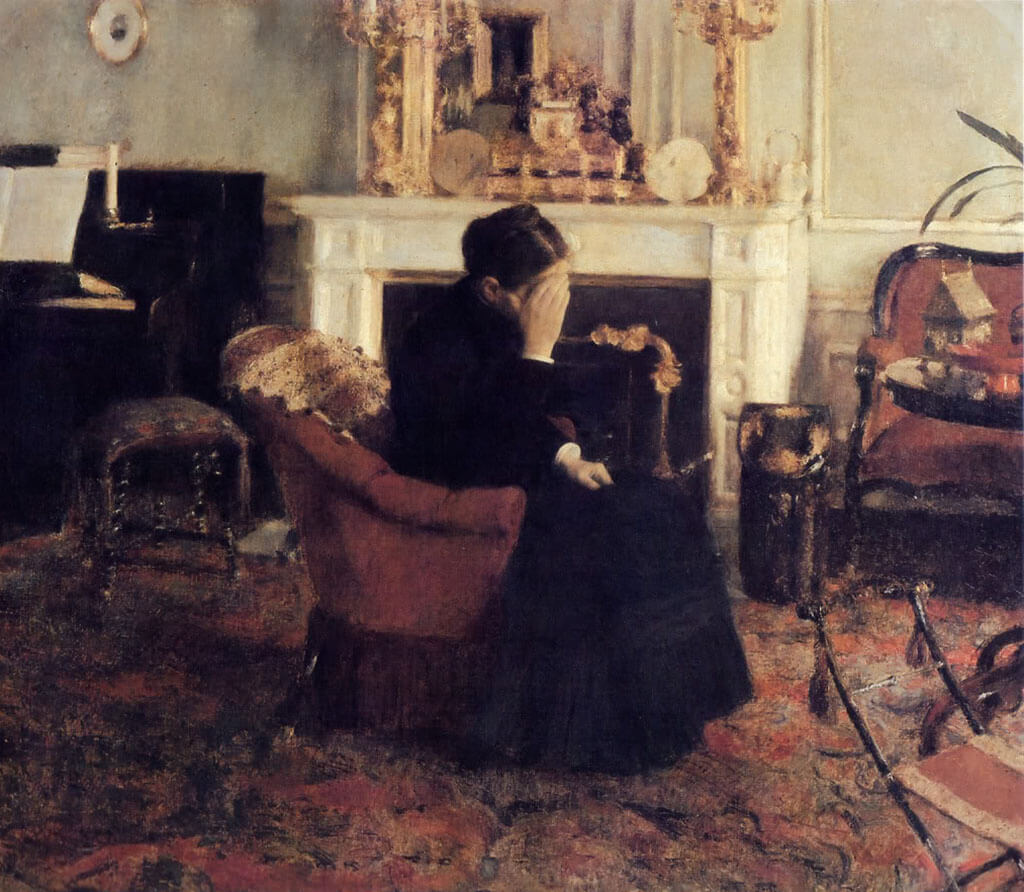

(Fernand Khnopff, Listening to Schumann [1883])

Producers who compose-record their own music spend a lot of time in critical listening mode. This is different from casual, everyday music listening, when the music washes over you and takes you into its space. Critical listening attempts to understand what’s really in play and at stake in a music by consciously analyzing, assessing, evaluating, and making judgments about how its sounds operate and whether they’re achieving something. In short, listening critically is the skill of being open to aesthetic seduction whilst keeping your head straight. Let’s consider two broad points about it.

First, critical listening often leads us to ask uncomfortable questions about our tracks in progress. Questions like: Are these chords interesting? Why does the beat sound annoying? Why does the music lack urgency? What are the sources of the murky mix problem?

Such questions arise in my work all the time, and I don’t know that I’ve ever successfully answered them. My solutions are always as ad hoc as my improvising is–fleeting and limited by my skills. I rely on tacit knowledge to move forward, somehow, on the continuum of this feels musically better than that. If, for example, drums sound annoying, I tinker with them until they sound closer to fascinating. If the chord progression isn’t enchanting, I take something out, move around a few notes, or just do another, more adventurous take. A fact about critical listening is that it’s without a map of precise artistic destinations. A counterweight fact about critical listening is that you can always trust your ears. If something sounds off or feels wrong, there’s a problem somewhere.

Because critical listening raises uncomfortable questions, two approaches help protect one’s composing from scrutiny. The first approach is to work quickly and non-judgmentally so that there’s little room for self-critique. A second approach goes the opposite way: work slowly and judgmentally–optimize now so that there’s less need for critical interventions later. For example, you might record a part quickly, in one take, but then immediately spend some time editing-finessing it before moving onto the next part. I find that most projects require a bit of both approaches.

A second broad point about critical listening is that it’s easier to sustain when you have some distance from your work. Our ideal positioning would be I really care about this music but I don’t care about what happens to it. One way to cultivate distance is to create in stages. Maybe finish a version 1.0 in one session and then put it aside for a while. When you return to the music after a few days or weeks you’ll be surprised that it has something…or maybe nothing. (I’ve hundreds of nothing pieces put aside, probably permanently.)

In sum, critical listening is a skill that musicians develop over time. The hours we spend listening closely to figure out what’s happening (or not happening) in a music gradually metamorphosize into a sensitive aural acuity for the feels of sound. More than instruments or virtuosity, critical listening is a musician’s most valuable tool.

Leave a comment