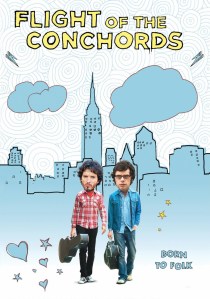

When I used to teach at a school on the Lower East Side, from 2007-2010, one day on my long walk on Houston Street from Avenue D to the 2nd Avenue subway stop I passed several actor trailers for the HBO show, Flight of the Conchords. The show, which ran for only two seasons, follows the zany and often surreal experiences of two musicians from New Zealand, Bret and Jemaine, as they try to make a career stateside with their folk-pop-electronic band, Flight of the Conchords. The show’s plots were absurd, its dialogue always deadpan yet unflinchingly earnest, and the music of the duo was a left-field, pitch-perfect pastiche of styles and parody of beloved artists, from Marvin Gay, Prince, and Bowie to Devo and the Pet Shop Boys. And, in an interesting case of reality imitating art, the Conchords were also a real life performing band that played songs from the HBO show, using a minimum of gear. (I once saw them perform at Forest Hills stadium.)

What made the Conchords funny? The positioning of their songs’ lyrics and narrative arcs anchored the humor. Humor is an outsider’s art, and here songs are play-by-play confessionals, their verses describing a situation matter of factly like a film script, which makes it seem like Bret and Jemaine are not totally inside the music but instead just outside it, narrating the very situations the music sets up. Another aspect of the Conchords’ humor is the musicality of their repertoire and how it smartly points to well-known classic songs without aping them. In the show Bret and Jemaine played an amateur-ish band, yet in the dream-like musical sequences they were effortlessly competent and funny. Finally, their music achieved novel things because it never obsessed about sounding “professional”—that most energy-killing of qualifiers used in the vicinity of art. Humor is the music of subverted expectations: it takes you by surprise and brings you into a singular world that makes you smile.

Leave a comment