“The Postmodern Condition was the result of a commission [Jean-François] Lyotard had accepted to write a report on the condition of knowledge for the Conseil des Universités of the government of Quebec, and his immediate worry was that universities were becoming corrupted by the unfettering of capitalism and the consequent reduction in the status of knowledge, from something whose pursuit was noble liberating to a mere commodity to be bought and sold. There were two stories, he supposed – one French, the other German – that universities had historically offered to justify what goes on in lecture theaters, seminar rooms and laboratories” (97).

“Education and learning were becoming, he feared, only instrumentally valuable, not intrinsically so. [Wilhelm von] Humboldt’s notion of pursuing science for its own sake was to become a casualty of post-modernism. ‘Knowledge ceases to be an end in itself’, wrote Lyotard” (98).

“Lyotard showed that it had been sick from the beginning. Lyotard supposed that the unfolding of the Enlightenment in tandem with the Industrial Revolution was not accidental. The latter supplied the former with technology. The laboratory needs money to perform its task since scientific instruments don’t come cheap. As a result, Lyotard argued, knowledge becomes a commodity: science may posture as objective inquiry, but is really in the hands of those with the most cash: ‘No money, no proof – and that means no verification of statements and no truth. The games of scientific language become the games of the rich, in which whoever is wealthiest has the best chance of being right. An equation between wealth, efficiency and truth is thus established’”(99).

“So how is science legitimated in the post-modern era? Lyotard’s answer was performativity. This is what Lyotard called the ‘technological criterion’ – the most efficient input/output ratio. Like everything else, knowledge has become primarily a saleable commodity, produced to be sold and consumed. What has been lost as a result is the aspiration to produce truth. The truth is expendable when knowledge is transposed into quanta of information” (105).

“While some have argued that post-modernism is a pre-digital phenomenon, many of the phenomena of post-modernism – especially the notions of simulacra, fakery, irrationality, scorn for truth and doubt about reality – have reached their apogees thanks to another desert that captivated [Jean] Baudrillard – namely, Silicon Valley” (254).

“Trapped alive in the web, we are fresh meat for big data. Social media companies are more than vast asset-stripping machines that feed off our anxieties, though they are that. They also offer performance spaces” (256).

“Post-modern irony is not liberating, but rather imprisoning. Lewis Hyde: ‘Irony has only emergency use. Carried over time, it is the voice of the trapped who have come to enjoy their cage’” (279)

“Society’s values, norms and ways of doing things change because of technology and how we are encouraged to use it. The dream of infinite choice and endless entertainment that these technologies seem to offer us also has its nightmarish flip-side: the tyranny of control. The difference between the modern age and the post-modern one is that we know what the steak is for, but we carry on drooling over it while we are ransacked – while our privacy is eliminated, our pockets picked, and our time exploited with a sophistication that would have astounded [Marshall] McLuhan” (294).

“[Friedrich] Kittler was right: the technology that seemed to extend our prosthetic reach in the world has facilitated our domination. Heads bowed in prayerful contemplation before our profane gods, we differ from our devout ancestors only in that we worship alone” (304).

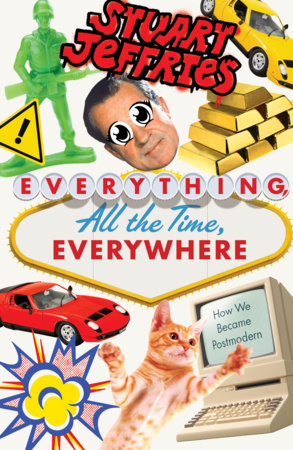

Stuart Jeffries, Everything, All the Time, Everywhere (2021)

Leave a comment