Every artist is their own curator. One curates at the level of sounds and sentences, parts and paragraphs, textures and timbres, arrangements and structures, finished tracks and essays. To curate is to be continually making decisions about what to keep and what to jettison, what to edit and re-arrange and what to leave just as it is. The goal is simple: get the good stuff out there and also, make sure that what gets out is actually good.

Curating is difficult because it involves making a lot of small decisions about a work’s quality, honestly answering the simple question, Does this move me? If I could avoid curating I would. But curating is necessary to keep track of what one has already done. Pieces in progress accumulate over the years, but their contents are hidden; like, what is this “Piano + Strings, November 1” anyway? I have no idea until I open the file and listen. Now that there’s hundreds of files, where do I begin?

I use several curating strategies. The first is to periodically open files, almost at random, to hear what’s there. Most of the time it’s disappointing: I’ll listen and think, No wonder I forgot about this. But sometimes I’m surprised. For example, recently I opened a piece and after five seconds of listening remembered having been excited by what I had begun. Whenever I’m surprised by the music, I start tweaking with its parts. The lead melody is obviously too quiet, the supporting chords are too loud, the pulsations need more treble…I make ad-hoc adjustments quickly, so as to not interfere with the main point of this curation strategy, which is to reacquaint myself with stuff. A compulsion to make adjustments is a good sign though: clearly I like the music enough to want to keep tinkering with it.

A second curating strategy is to swiftly finish a project that has potential. This is a powerful technique because it gets a work from an idea stage to being a tangible musical object. A useful approach to finishing is to do the least amount possible to get the music where it needs to go. Not every piece needs drums, multiple layers of reverb, or orchestrated strings. In fact, a piece that has a three or four parts may already have all that it needs. I might swap out a sound or add sweetening somewhere, but more impactful is making broad adjustments to tighten up an arrangement or a mix. For example, many tracks begin with everything happening at once, which is the worst possible way of introducing any idea. So I’ll mute parts, extend an intro, or fade in parts. And sometimes mixing is all the music needs. Mixing can be simplified: adjust volumes to be closer to correct, filter out unnecessary (and clashing) frequencies with EQ, shape the overall timbre of the mix, and add subtle compression so that every sound resounds clearly. Sometimes such adjustments can be done in minutes, not hours.

An important thing about fairly quickly finishing something–whether by arranging or mixing–is that it requires a shrewd mindset. You could spend 12 months on this four-minute piece or seven-paragraph blog post, but that’s not a very elegant way to spend one’s time. I often think, What can I do in the next twenty minutes to reshape this? Not tomorrow, not next year–in twenty minutes. Constraints force us to flex our taste and resourcefulness in the moment and take advantage of whatever serendipities this flexing may inspire. A shrewd mindset can also lead to insight about what a music needs. In recent months I finished some pieces I had long thought were unfinished because they lacked a beat. But whenever I added a beat I hated the sound. So maybe they never needed a beat in the first place? Every piece of music has its own needs, and often these needs are modest.

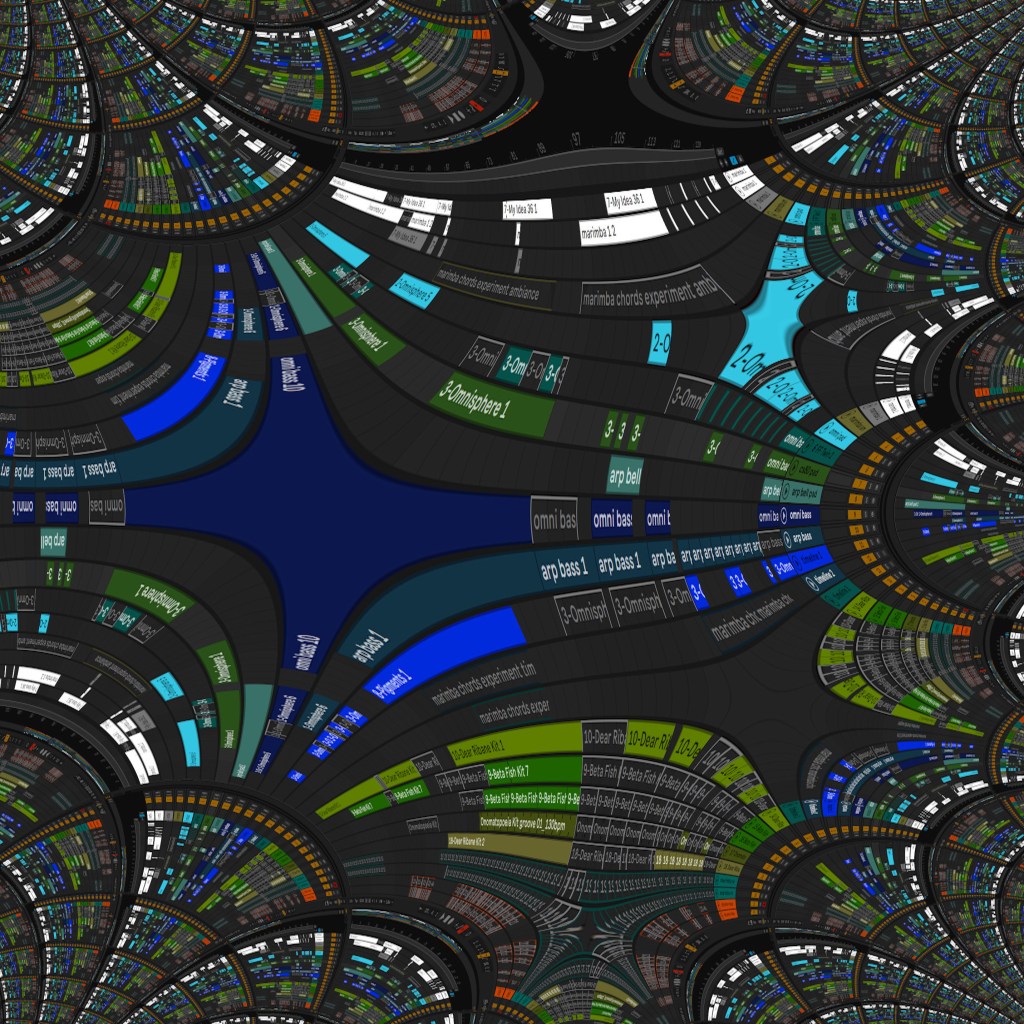

A third curating strategy is to think ahead of time about organizing your work before you dive in. Specifically, I almost never make random, one-off pieces for the reason that it’s almost impossible for future Tom to locate them. Instead I’ll make a bunch of tracks that share a musical element. For example, let’s say I’ve made something using a cool sound that I find expressive to play. I’ll save the piece using a title that references that sound. But it doesn’t stop there. The next day I might try to do something else with this same sound, or a variation of it. I’ll keep doing this for a few days or weeks until I have bunch of pieces that use the sound, or until I’ve lost interest. The process becomes fractal in that as I’m making new pieces I’m simultaneously curating that initial sound that inspired the series–playing with it, trying to understand it more, mutating it. Or maybe I keep that sound constant while I seek variations around it. It depends. I’m less concerned with how good any particular piece is than I am enjoying the flow of just doing another thing along these lines I’ve set up. Most importantly, from the standpoint of curation, is that I’m building a collection of related pieces that should be easy to find in the future.

A final point about curating is that it brings time in the creative equation by taking one out of a making mindset into an evaluative one. It’s easy to be self-critical, to say, Well, actually none of this music is that good: I hear problems everywhere. But curating your stuff is an opportunity to pause and take stock, to stretch time out, to hold on a second and think things through. Questions point us in the direction of answers. What are the issues you hear? What could make the material more compelling? What might you do to make this more like what you would want to listen to? Curation involves uncomfortable perceptions and difficult decisions about quality. But committing to improving your work–to improve not ideas about the thing, but the thing itself, as Wallace Stevens wrote –grounds your consciousness in the work’s actual world. Curating opens up a space, bringing us from it’s not that good to figuring out How can I refine this?

Leave a comment