Recently I’ve been remodeling music I haven’t yet released. I like the original tracks as they are, but remodeling is an opportunity to build a surprise, a chance to hear what happens when one’s prior work is bracketed and used as material for new music. The most exciting part of remodeling is defamiliarizing a track to the point that our knowing how it goes slips away. Suddenly, there’s an unfamiliar presence in front of you that’s holding your attention. Wow, how did that happen? With this in mind, let’s consider one of my remodeling processes.

I begin by searching for short sections of the music’s audio that can become individual looping parts for a new track. Using sampling-sequencing software, I scroll through the audio and manipulate it in simple ways. For example, I’ll transpose it to a lower register to change its pitch and slow it down. I’ll also filter it so that it’s all opaque low frequencies, all brittle treble frequencies, or somewhere in between. Often such simple manipulations lead to striking results.

Finding a first part is key because it’s the starting point. The part can be anything, but it needs to benefit from repetition, not suffer from it. It needs to work as a loop you can listen to for a long time. And it shouldn’t say too much–it should leave room for the other, as yet undiscovered parts. Sometimes I find a first part in a strange place, like the very end of the audio file as the music is fading out.

With a first part located and committed to, next I figure out second and third parts. These parts need to both complement the first–as if a response to its call–and also contrast with it. Ideally, each of the three parts will do their own thing whilst interlocking with the others. There are two facets to this. The first is that I’m positioning each part at a different point in the rhythmic cycle so that the three of them just barely overlap. Second, each part will shift slightly and continuously through the piece. Parts should, I think, always do something, even if they’re looping, so that they tell their own story. One way I achieve this–without altering the rhythmic cycle or the positioning of the parts within it–is by offsetting a part’s sample start point over time. For example, if part 2 catches the beginning of a chord sequence, I’ll make variations of it by incrementally moving its start point slightly forward or back. This way, variation 1 might begin halfway through the first chord, variation 2 at the first chord’s tail end, and variation 3 at the onset of the second chord, and so on. It’s like taking a series of photos of a scene, but moving the camera a bit each time to capture a multitude of viewpoints.

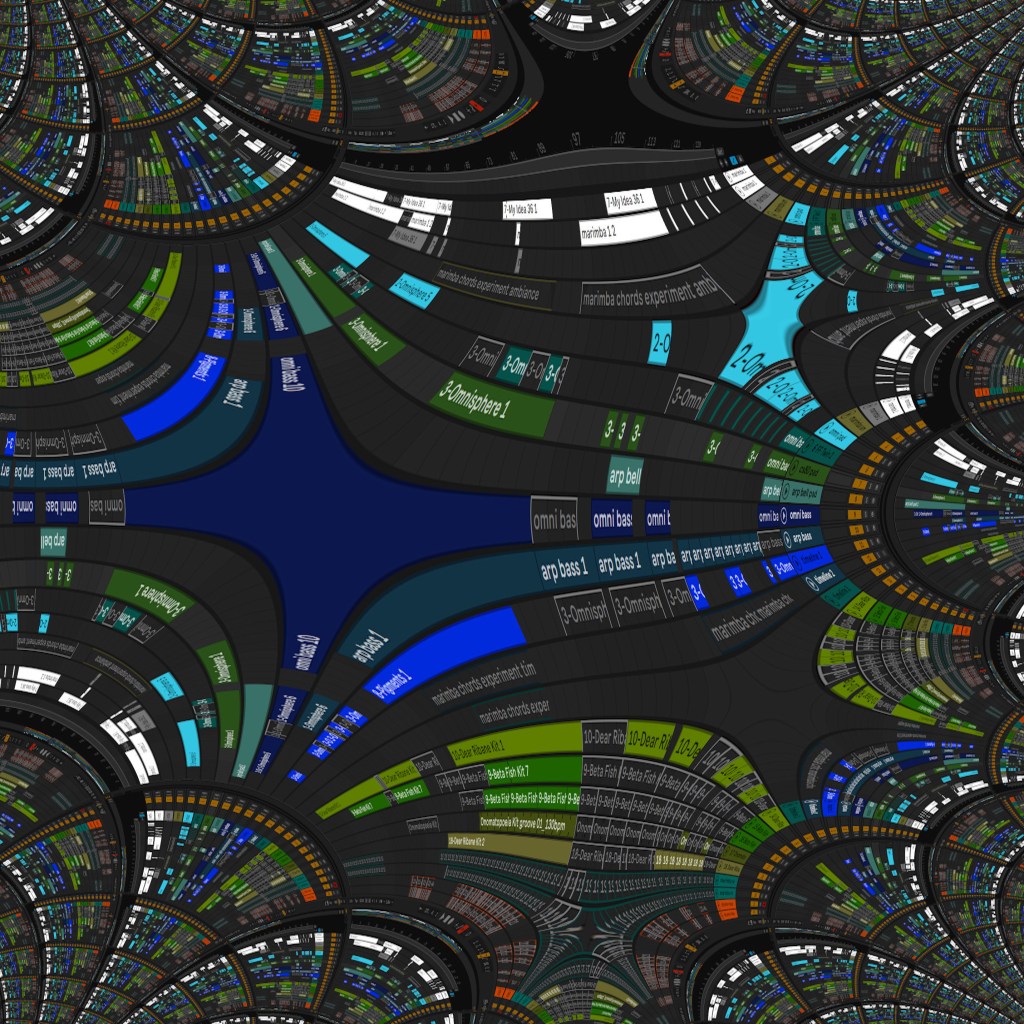

When we take into account all of a part’s potential starting point variations, suddenly there’s a lot of options! I try to try out every promising-sounding variation and make note of their location in the audio file (e.g. 4.76, 5.1, 45.3…) until I’ve gone through the entire file. It’s tedious, sometimes to the point that I’ll skip around until something good happens. But what makes variation-finding worthwhile is that it generates a library of cool-sounding samples.

I’ll repeat this process for part 3, but this time I’m cross-checking the part’s variations against those of parts 2 and 1 (which is often kept constant) to make sure everything goes together. It’s during this repeated listening that I delete variations that don’t work. Or I notice that say, variation 16 of part 1 would actually make a better starting point for the part’s variations sequence, so I reverse my list of numbers and begin with 16. Or I notice that part 3 really only has three variations to part 1’s six. Could part 3 then, stay on each variation for twice as long so everything lines up? I try it to hear if it works. Occasionally it’s clear that parts 2 and 3 are in the wrong place in the rhythmic cycle: part 2 should come after, not before, part 3, so I swap them.

I’m figuring out these kinds of compatibility issues now because that the next step is recording the three parts as a performance that moves along the series of variations I’ve decided on. For me, composition’s main thing is not orchestration or grand textures, but simply getting a structure right. When the structure is right, the three parts I’ve committed to appear to talk to one another and their harmonies co-resonate and overlap on a shared frequency of feeling. I record each part, one at a time, onto its own audio track, performing the track’s variations by cueing up the different sample locations just before the onset of the part’s repeat point. It’s a little five minute performance! I’m nervous, poised with my finger on the “>” key to move the sample point (You have one job, Tom) counting bars of emptiness as my mind wanders (One job), until the next cycle comes around. It’s almost as bad as counting measures at the back of an orchestra as you wait for your entrance.

With the three parts recorded, I place them along the stereo field so that part 1 is in the middle, and parts 2 and 3 panned left and right. Now I add bits of effects to make each part the best version of itself and gel with the others. This doesn’t mean that I’m going for high-fidelity, though. (A topic for another time, but a high-resolution aesthetic in music production can sound grotesque.) I’m going more for vibe and texture. Since I’m working with samples of my own work, there’s already some built-in vibe. But it depends on the piece: sometimes the audio is dry, sometimes it’s reverb’ed. The technique I use most is adding effects gradually and, if possible, subliminally, so you feel them before noticing them. An example of this is a reverb that slowly increases, an EQ that moves around, a hint of a drifting resonant peak, or a narrowing stereo width instead of a volume fade to suggest the denouement of a piece.

In sum, all of this part-finding, variation-making, recording, and arranging takes the remodel some distance from the original upon which it’s based. Of course, I can still hear some of the original music here and there, but I love it when the original has faded, when it’s like a dream recollected. Fragmented like memories, now this new music does its own thing. Sometimes the more we don’t recognize a music’s source, the more exciting it is to listen to it.

Leave a comment