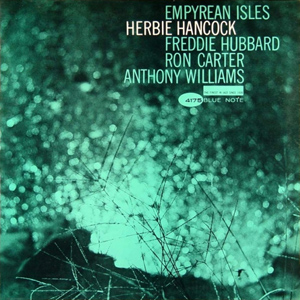

For three or four years when I was a teenager I bicycled on weekends to second hand record stores, searching for jazz albums I had read about or listened to on late night FM radio. Mostly I was interested in the drummers on these albums—Tony Williams, Max Roach, Jack DeJohnnette, Roy Haynes, Baby Dodds, Papa Jo Jones, and other architects of twentieth century jazz drumming. I listened to the albums focusing on the qualities of the drumming more than anything else, determined to learn something about and from them. One of these albums was Herbie Hancock’s 1964 recording Empyrean Isles, whose track “Cantaloupe Island” I studied and played along to, somehow with little curiosity about Herbie’s infectious piano riff (which sounded like a sample) or Ron Carter’s four-note rising bass line anchor. Instead, for me the star of the show was Tony Williams’ energized drumming, and over time I noticed qualities in it. His ride cymbal pattern was not a typical swinging triplet pattern, but rather a “straight” steady eighth note propulsion; he pedaled the hi hat on every quarter note beat, whilst his right foot and left hand played a simple kick and snare pattern—1-and-(2)-and-(3 and 4) and-ah—whose call and response syncopation moved like a fluid drum machine; and at the end of the song’s 12-bar phrase, Williams landed an emphatic rimshot on beat four (and mis-hit it the second time around, at 1:09).

After figuring it out at slow speed, Williams’ “Cantaloupe Island” beat was within my wheelhouse to play, and I played it often as a kind of solo against an imagined band. As I played other details in Williams’ drumming I had noticed on the recording came to mind. Williams’ bass drum’s sound was not the dead “thud” of rock drummers’ kits, but rather a resonating higher pitched sound, and I retuned my bass drum to try to match it, feeling how the drum without muffling material had a more lively response to my foot. There were occasional stutters in Williams’ ride cymbal and snare drum parts too, where he played an 8th-note double-time to make it two 16ths, or paused his hand for a microsecond, without interrupting the musical time. He also used buzz rolls on toms for fills (2:49) and fragmented the beat at places, as if he were singing the song’s melody and not drumming its rhythm (3:25). So began my unwiring from rock and pop drumming’s heavy-handed thump, as I learned Williams’ light and skittering ad libs by heart and expanded my drumming vocabulary, one detail at a time. From Empyrean Isles and many other jazz albums I listened to during those years, I learned to notice qualities apparent in drummers’ touch, drum tuning, phrasing, and musicianship.

Leave a reply to Russell Hartenberger Cancel reply